Elections as Entry Points for Collective Action#

Civic organizers and activists work to find strategic political entry points that present the most viable engagement avenues and opportunities in a given context. When they are held, elections provide a viable entry point for individual and collective citizen participation. They are a fundamental democratic process that allows citizens to vote for alternative parties, platforms and leaders. At the same time, election periods offer a unique opportunity for citizen groups to raise policy issues, secure commitments from candidates, build relations with like-minded groups and individuals, mobilize activists, and increase the visibility of their issue or cause.

Yet elections are often treated by donors and development practitioners as discrete events requiring process-oriented support (i.e., helping ensure democratic standards are met in terms of registration, campaigning, voting, counting, etc). There has been much less emphasis on putting elections to work to advance the collective socio-economic interests of citizens. Financial or technical support to strengthen an election process may result in one that is more inclusive and fair, but even the most credible elections do not guarantee a government that will address citizen needs.

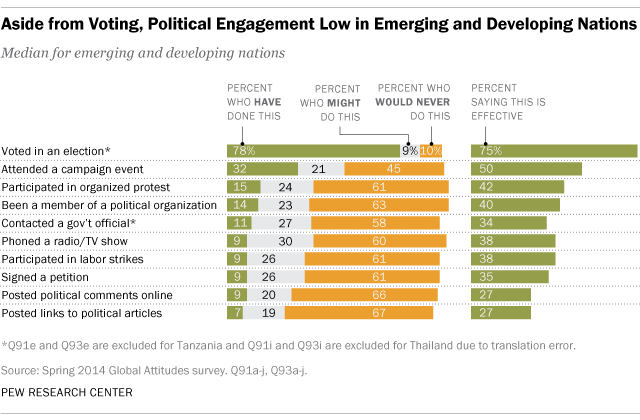

At an individual level, elections provide a way for voters to elect leaders to represent their interests. A recent Pew survey shows that, in general, citizens in large numbers participate in elections, which are viewed as an effective way to promote government accountability. In the 32 developing countries included in the survey, voting was the most frequently cited mode of political engagement, with a median of 78 percent responding that they had voted in previous elections. Moreover, at 75 percent, voting was most often cited as an effective way to influence government decision making. This statistic indicates that even in less-developed democracies, with immature or vague processes, elections are viewed as a systematic, regular way for citizens to register their satisfaction with leaders or demand a change.

Elections also offer a political space that can be leveraged by citizens and civic groups working collectively on an issue or cause. This might include relationship building by identifying policy priorities and getting voters and candidates together to discuss policy positions. When political parties and candidates are competing for votes, they are often more open to interactions with citizens, and can be pressed to make commitments. This can set the stage for post-election citizen engagement designed to hold newly-elected leaders accountable for their campaign promises, or to work with them on agreed upon priorities. According to the same Pew survey, 32 percent of the respondents reported that they had attended a campaign rally, making it the second most popular form of civic participation. These figures indicate that although political participation is relatively low in many countries, when people do seek to engage in politics, they view elections as a primary opportunity.

Elements of a Strategic Campaign#

This study sought to document the value of incorporating elections into “strategic campaigns” for accountability. In practice, a strategic campaign combines a variety of actions over time to influence decision makers. This is distinct from an approach that relies on a single type of tool or action, such as a grading public services or tracking expenditures. These approaches may result in some limited progress, such as improved understanding or greater transparency, but often fall short of creating the pressure needed to hold government to account.

Practically speaking, campaigns that succeed are those that focus on the power dynamics surrounding the issue being addressed. To influence those dynamics, campaigns require a strategy and a plan involving an iterative series of actions that might extend across the political cycle, including election periods. The country cases described in this study illustrate how NDI’s local partners developed winning strategies and made plans to take advantage of the space provided by elections. In each case, groups framed the problem, proposed solutions, found evidence to support their position, built alliances, established relationships with decision makers and forced a response through multiple actions.

| A Strategic Campaign... | |

|---|---|

|

Combines Multiple Actions |

|

|

Builds Multiple Relationships |

|

|

Exploits Multiple Entry Points |

|

| ➧ |

Combines Multiple Actions |

➧ |

|

|

A Strategic Campaign... |

➧ |

Builds Multiple Relationships |

➧ |

|

| ➧ |

Exploits Multiple Entry Points |

➧ |

|