For advocacy efforts to really make sustained improvements in people’s lives, activists need to take into account the power imbalances that block change and adopt politically aware strategies to address them. Elections can be an important component of such strategies. The following recommendations are offered to democracy and governance practitioners and development professionals seeking to implement programs that support efforts of civic groups to effect change through politics. For more context, check out the Country Cases on this site.

Understand the Political System#

When it comes to making change, context matters. Activists will find little success if they do not understand the basic shape of the political system they are operating in and how to navigate it. To start, groups need to determine which level of government is responsible for addressing their issue. In Malawi, for example, some aspects of community development planning have devolved to the local level, so Tiphedzane targeted its advocacy efforts at ward councilors. At the same time, the group knew that funding decisions were made at the national level, so it sought to build relationships with members of parliament as well. In Macedonia, authority for ratification of the CRPD was held by the national legislature, so Poraka targeted its demands toward national party leaders during the campaign for members of parliament.

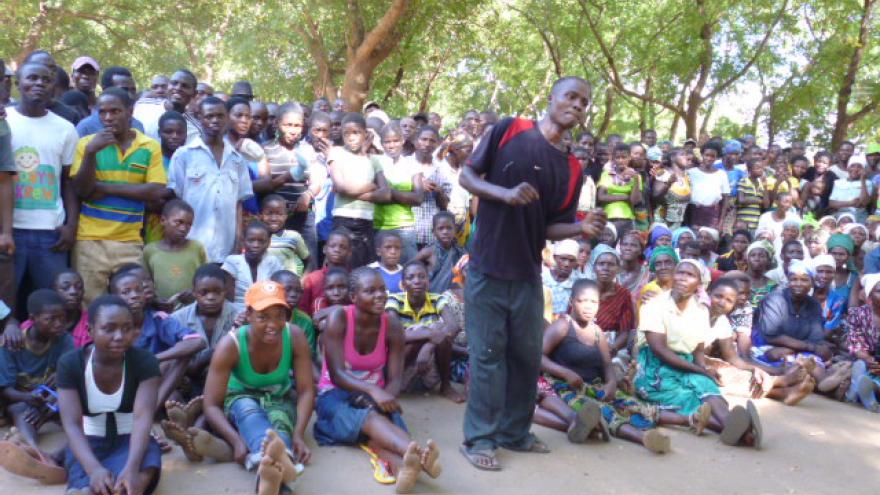

Groups also need to be aware of which parts of government have jurisdiction over a given issue. In most countries, this requires an understanding of the roles and responsibilities of the executive branch and ministries on one hand and the legislature on the other. Perhaps even more important is to understand how formal and informal power is divided up among these branches and how oversight is (or is not) exercised. For example, in Malawi, the local ward councilors have a formal role to play in overseeing how local development plans are created. However, because local councils had not been elected for so many years, representatives in the local offices of various line ministries had cultivated a great deal of power and influence. These unelected representatives had little incentive to provide civic groups with information about development planning and documents. Following the local elections, however, Tiphedzane was able to leverage its burgeoning relationship with the new ward councilors to gain access to development processes. This new engagement helped to establish greater citizen participation in local decision making and more robust legislative oversight.

Figure Out: How Does Change Happen?#

Any effort to fight for progress on issues must begin with a theory about how change happens. Citizens need to develop an understanding about how power is aligned within the government and how they can enhance their ability to demand change. This requires groups to master a variety of skills and capacities that will help them navigate the contours of formal and informal political processes. These include strategic planning; mapping the political terrain; identifying advocacy targets, allies and opponents; establishing linkages between political events and advocacy issues; building relationships; developing credible narratives;and drawing on evidence to support policy positions.

In many countries, especially those with younger democratic systems, election periods are unique in that they provide fertile ground for groups to sharpen their understanding of how change happens. This opening allows groups to experiment with different forms of activism and engage with voters and decision makers. Civic groups may find the following questions to be helpful in assessing how activism during an election period could fit into a longer-term strategy for change.

- What kind of elections will be taking place (e.g. local, presidential, parliamentary)?

- Which organizations or groups of people have a specific set of issues they have been working on? Or is there a well-defined constituency (e.g. women, youth, specific community)?

- What issues do citizens care most about (e.g., public health, water and sanitation, education)?

- What issues are dominating the political agenda (e.g., EU accession, extractive industry oversight)?

- Are there existing mechanisms for citizen engagement with candidates and/or political parties (e.g. debates, town hall meetings, rallies)?

The Malawi case study illustrates how Tiphedzane took advantage of gains made during the election period to hone its strategy to have new boreholes dug. Through its election activism, it was better able to understand formal and informal processes that drive local development initiatives. At the same time, it built relationships, conducted public outreach and used a variety of tactics to achieve its goal. Looking forward, Tiphedzane will be better placed to navigate the complex dynamics of future social change initiatives because of its election experience. In Turkey, activists knew their demands for more limited government would not be addressed unless they were able to mobilize widespread popular support to pressure leaders for reform. The Checks and Balances Network emerged to cultivate a national movement of groups that possesed the power and influence to fight for government response on these issues.

Plan for the Long Term and Look for Entry Points#

Social change takes time and activists need to plan for the long term by taking advantage of a variety of entry points. These can be described simply as opportunities for meaningful engagement between decision makers and citizens. Often they take the form of openings for citizens to access political processes, such as budget deliberations, a constitutional review or an election. Every political environment is different and may present different opportunities for engagement. So activists should consider the political context they are working in and be strategic about choosing which entry points to exploit.

Activists from Poraka in Macedonia demonstrated this skill. They had been doing well building grassroots support for disability issues through their local chapters, but once parliamentary elections were called, they quickly adapted their strategy to take advantage of the new opportunity. By encouraging political parties to sign pledge cards to support ratification of the CRPD, they were able to complement the gains made in their grassroots efforts with decision-maker support. They knew that candidates competing for votes might be more willing to listen to citizen concerns and make commitments to address them.

Develop Relationships and Act Collectively#

During elections, when political parties and candidates are competing for votes, they are more likely to be open to interactions with citizens and can be pressed to make commitments. Activism undertaken during election periods has the potential to help groups develop relationships with leaders that can create pathways for change on key issues. In all of the country cases in Malawi, Macedonia and Turkey, for example, the election period offered new and rare opportunities for activists to engage with candidates, political party leaders and the government. Through these interactions, groups came to be seen as credible representatives of their communities or constituent groups and were able to demonstrate expertise on their priority issues. Elected local officials came to view these organizations as solution-driven interlocutors worthy of their time and interest.

Elections also provide a context for activists to build relationships with voters by organizing for change on issues that are important to them. Such collective action can be easier during election periods than at other times in the political cycle. Citizens may be motivated to work together to organize a debate, participate in a community mapping session, publish an issue paper or educate voters because they can see how their efforts connect with and influence the political process. For example, in Malawi, citizens worked together to organize debates for local government candidates. Many citizens chose to participate in these initiatives because it provided a unique opportunity to question candidates and press them to commit to addressing them once in office.

Finally, elections may provide a hook for groups to build alliances or networks with other organizations on issues of common interest. In Turkey, for example, the diverse organizations of the Checks and Balances Network came together around the presidential election to address issues related to limited government and transparency. Each of these groups focuses on its own issues day-to-day, but by working together, they were able to address systemic political challenges that were negativly impacting the potential for quality-of-life reform in many areas.

Consider Organizing Around an Issue or Cause#

Research from the Overseas Development Institute shows that citizens, particularly in lower-income countries, tend to value government action on quality of life issues, such as education, health care and employment, over abstract democratic principles. Citizens value democracy, but they are much more likely to demand and defend it if it responds to their needs. For this reason, groups looking to mobilize participation in elections may be more successful if they incorporate voter information and get-out-the-vote efforts into broader issue-focused campaigns. This was the approach taken by Front and GoGreen in their Cool Mayors campaign. They reached out to potential voters on the environmental concern and wove in messages about the importance of participating in the election.

An issue-based approach is distinct from traditional voter education projects that emphasize the quality of the election and voter participation, and employ messages about rights and responsibilities such as, “your vote is your power.” Mobilizing people to vote based on specific issues paves the way for activism that extends beyond the election. In Malawi, Tiphedzane asked candidates to sign social contracts committing them to addressing important community issues if they were elected. After the election, citizens said they felt empowered to hold newly elected lawmakers to account for those promises as a result of the contract.

Conventional wisdom in many countries points to apathy as a common explanation for low voter turnout. In such situations, educating people about how to vote or reminding them that it is their right to vote may not be the most effective strategy. In circumstances like these, activists should consider issue-based approaches to motivate people to go to the polls by connecting quality-of-life priorities to the political process.

Employ a Range of Tools and Tactics#

Once a group has decided on a strategy that focuses on issue organizing, the next step is to identify tactics and tools that will help them achieve their goal. The most effective campaigns use a combination of tactics and tools that they deploy strategically depending on the target audience and the political entry point they are organizing around. Tactics could include participatory research, such as focus groups, surveys or community mapping. Or mobilizing events, such as debates, rallies and marches, may help attract people to their cause. Elections often invite opportunities for voter education when radio broadcasts, group meetings, canvassing, literature drops and social media may be useful tactics. Finally, outreach to the media through press conferences or press release are other ways to engage voters on issues. In Malawi, Tiphedzane chose to focus on mobilizing voters through community mapping issue identification exercises and candidate debates. While in Macedonia, Poraka chose to reach out to candidates with campaign pledges. In Turkey, CBN developed a series of policy briefs aimed at political and media leaders to educate them on the issue of transparency and limited government.

However, it is important not to rush to select tactics and tools before a strategy has been chosen. Tools that take advantage of the Internet and social media can be particularly enthralling with promises to streamline communication or mobilize supporters. While it may be tempting to forgo the difficult work of planning strategy, this preliminary step is essential to ensure that tactics are employed effectively and that they contribute to the desired outcomes. Despite these challenges, choosing tactics and tools provides opportunities for creativity and innovation. Matching them correctly with campaign strategy ensures they will contribute to the campaign goals.